Image Change: Shifting Images, Shifting Behaviour

Shifting Images, Shifting Behaviour

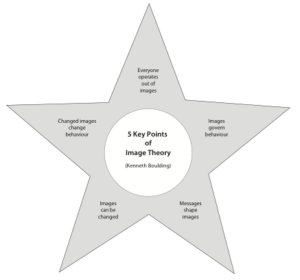

The concept of the image shift has been around a long time. Perhaps professor, poet and activist Kenneth Boulding, author of The Image, best conceptualized the process of image change. Boulding’s process can be captured in a few sentences:

- Everyone operates out of images of themselves and the world.

- People’s images determine their behaviour.

- Images can be changed by new messages.

- When images are changed, behaviour changes.

What does this look like? Some of us remember the radical anti-smoking health films shown beginning in the late 1960s. Smoking was still very much the “in” thing; just about everyone smoked something. Then came this graphic film depicting the horrendous state of a smoker’s lungs with lung cancer. Suddenly the invisible had become visible, and for some, the image shift was immediate. The phases of the image shift went like this:

- old image: just about everybody smokes, so it must be OK.

- message: this is what smoking can lead to: lungs that look like a coal cellar.

- new image: my lungs look like that! That is horrible. This is not acceptable.

- behaviour shift: I quit. I am now a non-smoker, and an unordained evangelist on behalf of quitting smoking.

Unfortunately, only some people responded like this. Denial can set in very fast. For other smokers who saw the film, the process was more like this:

- old image: just about everybody smokes, so it must be OK.

- message: this is what smoking can lead to: lungs that look like a coal cellar.

- new image: some smokers’ lungs look like that! I had no idea.That’s awful.

- resistance: But I’m special. And young. And I smoke filter cigarettes. It won’t affect me like that.

- behaviour shift: None.

Perhaps for them, it will take the development of a permanent, bone-jarring, hacking cough. Or worse.

Another example: The newspaper reported recently that a group of Bay Street stockbrokers had paid a visit to a shelter for the most deprived homeless in Toronto when the normal inhabitants were not there. They were radically affected; the sight of the poor surroundings and minimal furnishings went straight to their hearts. They had been transported from one world to quite a different world. Their big bucks, high tech, quick money image of the world had shifted to include that of no bucks, no tech and slow money. They had certainly experienced an image-shifting situation. Previously, “the homeless” was an economic reality; suddenly, it became a category of humanness and a summons to compassion. (Perhaps next time they will meet some homeless people, too.)

Of course, as Boulding goes on to point out, the process of image change is not mechanical. When images have been deeply held and nurtured over years or decades, one clearly delivered message can rarely cause an image shift. Boulding points out three results of message delivery:

- the image may remain unaffected.

- the image may be altered by simple addition; not an image shift, but I know more than I knew before. For example I knew that the Black Hills were in western USA; I know now, in addition, that they are in South Dakota. A lot of what we call education involves this simple add-on of facts about the world.

- sometimes a message hits some sort of nucleus or supporting structure in the image, and the whole thing changes in a quite radical way. The image shift that happened to Saul on the road to Damascus is a dramatic example of this.

It is this level of image shift, for example, that some travellers (not tourists) visiting places like Bangladesh for the first time have experienced. They may describe on several levels—intellectual, emotional and physical shock, often followed by the statement, “I had no idea!”, followed by many attempts to grasp the meaning of it all; finally feeling that their whole life style has to change.

What makes images difficult to shift is the value that we twine about them. If, for example, I just love double-cheese, half-pound hamburgers, and a friend points out the deleterious effects of eating such delights, his message will come to me as hostile to my image of what’s good to eat, and I will resist accepting it. Similarly, if a wife insinuates to her golf-loving husband that he might think of spending less time at the golf course and more time with the kids, there will also be resistance. Both these examples require a shift in values and priorities.

Resistance usually takes the form of ignoring the message—the hamburger lover says, “I’ll wait till a doctor tells me to give up junk food”; the golf-lover ignores his wife’s message with “Yeah, we need to talk about this some time,” as he walks out the door with his clubs. The wall of resistance may be broken down with the cumulative effect of repeated messages. Sometimes the wall tumbles down when a message is delivered with great force and authority, as in the following example from a counselling situation.

A colleague employed as a counselor on a university campus tells this story of an undergraduate woman who came for counselling. An interesting part of the student’s profile was that she had a long neck—a really long neck. She was quite a sight walking across the quadrangle. She tried to hide her long neck with a hang-dog posture and by draping her long hair all round her head. Her clothes were trampy; her feet scraped along the pavement. Every week she came to the counsellor to talk about all her problems. The counsellor would attempt to draw out from her what was at the bottom of these problems, but the process seemed to be going nowhere. Finally, on a Friday afternoon the situation blew up. The counsellor was tired at the end of a hard week, and when the undergrad came in, something inside the counsellor rebelled against the normal questioning process, and, instead, out came an explosion of rage: ‘Look, this is ridiculous! You want to know what your problem is? Your problem is that you are a long-necked girl, and you hate being the long-necked girl that you are. That’s your problem.” Her response was fast and vicious. She lashed out, and left four parallel scratches along her counsellor’s right cheek, and ran away.

In the counsellor’s mind, the student was a lost cause. She would never come back. Six months later the counsellor was sitting in her office looking out the window when an apparition swam before her eyes. The problem undergrad was walking across the lawn, but she looked different; she had piled up her hair, honeycomb-style; her head was held high, her clothes looked new and just right, and her long neck was gloriously exposed and looked even longer. She looked like a million dollars. It was obvious that something radical had happened. The outburst had struck a chord. It had taken six months of processing, but now the image shift was obvious in her behaviour. The long-necked girl had decided not to hide who she was but to celebrate it. Applying Boulding’s formula to the story might yield an analysis like this:

- Image: I cannot live my life because I have a long neck.

- Message: all your problems stem from the fact that you do indeed have a long neck and you don’t want to be the long-necked one that you are.

- New image: My long neck is part of who I am and I can live with it.

- New behaviour: Walking tall, taking care of herself; new sense of confidence.

Those situations where we have our images challenged are moments of great possibility—we have the option to be freed up from the past and move into the future. But there is nothing automatic about the image-shifting process. When a message breaks through the wall of resistance, we may decide to dialogue with the new image. But, then again, we may deny its relevance, finding it offensive. The offense is intellectual: “This just can’t be true; I’ve lived like this for 20 years.” The offence is also emotional: “How dare he say that to me! I know how to run my own life.” And it is also decisional: “I don’t want to hear this message, because I don’t want to change!” Saying yes to the new image is a free decision. But when the decision to change the self-image is freely taken, it is the key that opens up behavioural or stylistic changes.

How does all of this relate to facilitation?

When people encounter ToP™ facilitation methods for the first time, they are often so taken up with trying to grasp the details of the method, that they do not have time to grasp the set of image shifts that these methods embrace. But everyone being trained in these methods is asked to subscribe to five major image shifts in the process of leading or joining in participatory conversations or workshops.

- Everyone has wisdom.

- We need everyone’s wisdom for the wisest result.

- The wisdom of the whole group is greater than the sum of the parts of the group.

- Everyone gets to hear and be heard.

- There are no wrong answers. This is really a shorthand way of saying: “I recognize this person’s experience of life as authentic. There is a reason for their answer which comes from their life. If I don’t understand or agree with it, I can honestly say so and ask for clarification.”

Imagine the impact if these five simple presuppositions were on wall posters in every organization. Imagine what it would be like if workplaces operated out of these assumptions.

Leaders, for example, instead of managing people through their command over “the right answer,” would try to come up with the right questions to facilitate answers and commitment from their employees. They would understand that one “right” answer requires many perspectives. Then, instead of barking, “Just the facts, please!” manager facilitators would ask for the implications of the facts. Instead of hearing that so-and-so is assigned to come up with a plan, workers would get used to planning in meetings. Instead of meetings invariably resulting in arguments, they would be seen as participatory discussions. Instead of the rather arrogant argument, “Why meet? I know what needs to be done,” everyone would see clearly how productive meetings generate commitment and take less time in the end than other approaches.

Instead of the image that “all power resides in the boss,” the perception would grow that the power really does lie in the centre of the meeting table. In place of the image that we grow by finding out the truth, we would feel ourselves growing by appreciating different viewpoints. Instead of the image that consensus means that everyone agrees, people would understand that they don’t have to agree to be able to dialogue creatively. Instead of employees being regarded as the “great uninformed,” they would be seen as the experts, whose scope of responsibility has been enlarged by participative methods.

“Facilitation,” one practitioner has written, “is much, much more than a new tool, or a kit bag; or a new management arrow in one’s professional quiver; it is a life skill. Finally, we reach a different understanding when we get beneath the wisdom to what the discipline is saying about the way life is. Here the decision about facilitation is a decision about a new style of life.”

It is one thing to facilitate in a corporation or a service agency with the image that you are using a “neat” participatory method to help them plan or solve problems. It is quite a different thing to image that through one’s skill with the methods, one can shift the image of what is possible for an organization’s structure, meetings, and ways of relating and working—in fact, all of their workplace operating images.

To quote Laura Spencer, author of Winning Through Participation: (p. 23) “Participation is not just a gewgaw bolted onto the management machinery by social engineers, as… many firms have done. Nor is it ‘installed’ as if it were a muffler on a car…True participation is not a program. It is a whole different way of dealing with people. Introducing participation into an organization’s operations does not add something new—it transforms the existing mode of operation.” Image shifts are possible whenever a facilitator sets up an easel, picks up a marker at the front of the room, and says to a gathered group, “Let’s brainstorm the issues facing us and decide together how we can deal with them.” Out of such invitations can come a series of image shifts than can revolutionize the workplace.

Facilitator as Image Shifter by R. Brian Stanfield © 1996 Edges: New Planetary Patterns. Reprinted with permission.

We teach methods that go with this concept in the Human Development course, and touch on how to use it in the environment for facilitation in the Art and Science of Participation course.